Many business people assume that they and their team are very good at problem-solving. However, most organizations do not struggle with problem-solving, but in understanding the actual problems.

Surveys show that 85% of C-suite executives believe that their organization performs poorly at problem diagnosis, and 87% agree that this deficiency comes at a significant cost. Encouraged to take action, managers often look directly for a solution without the confidence that they understand the actual problem.

More than 40 years ago, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi and Jacob Getzels demonstrated the central role of problem framing in creativity in the book, “The Creative Vision: A longitudinal study of problem finding in art”.

So why do companies continue to struggle with problem diagnosis?

Thomas Wedell-Wedellsborg in his article “Are you solving the right problems?“, attempts to answer this problem and offers suggestions to overcome the challenge.

Problem: Overengineering the diagnostic process

Methods such as Lean Six-Sigma, Scrum and others can be advantageous. However, their all-encompassing nature can make the process too complex and overly time-consuming. Team members often need to take action daily, rather than yearly… so simpler methods are required, ones which don’t require months of training.

Problem: Over-simplified techniques

Thomas Wedell-Wedellsborg states when people use simple techniques, such as the “root cause” analysis, or the 5 Whys, they often find themselves digging deeper into the problem rather than finding a diagnosis.

Solution: Alternative Definition

The author states that creative solutions nearly always come from an alternative definition of the problem. Therefore, he offers a new approach to problem diagnosis; reframing, which took almost ten years to develop with his colleague Paddy Miller.

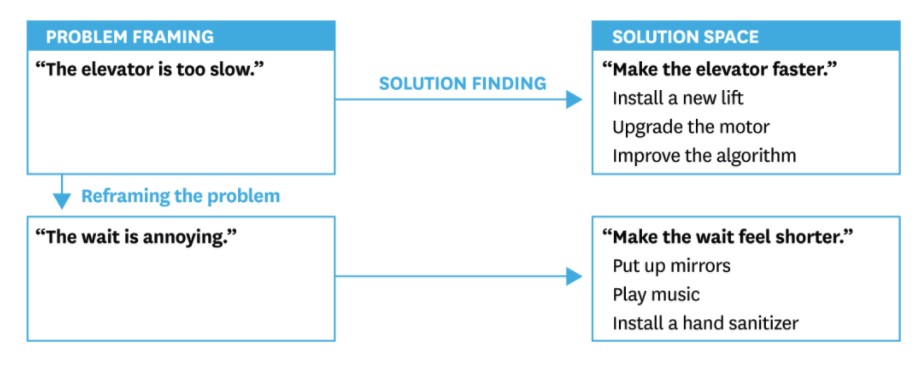

Let’s use an example to contextualize what reframing is trying to achieve.

THE SLOW ELEVATOR PROBLEM

Situation: You are the owner of an office building, and most of your tenants are complaining about the elevator. It’s old and slow. They are threatening to break their leases if you don’t fix the problem.

Most people, when asked, can quickly give some solutions, such as replacing the lift, changing the motors or upgrading the algorithm which runs the elevator.

The author calls it “a solution space”: a cluster of solutions that share assumptions of what is the problem.

On the other hand, when consulting building managers, they presented a different solution: install mirrors next to the elevator. This simple measure showed significant results in reducing complaints because people lose track of time while staring at something fascinating… themselves.

The mirror solution is interesting because it does not solve the stated problem. Instead of making the elevator faster, it offers a different understanding of the problem. The first problem definition is not wrong.

Reframing is not about finding the “real” problem, but seeing if there is a better problem to solve.

Therefore, Thomas Wedell-Wedellsborg presents Seven Practices for Effective Reframing. He suggests two ways of applying the method. One of them is to methodically implement all the practices if you have time and control over the situation (what can be accomplished in about 30 minutes). The second way, in cases when you don’t have much control over the situation, is to choose one or two practices that are more suitable to the situation (perhaps a team member ambushes you in the hallway, and you have only five minutes to help him).

THE SEVEN PRACTICES FOR EFFECTIVE REFRAMING

- Establish legitimacy – It is difficult to use reframing if you are the only person in the room who understands the method. Show them this article, or relate the slow elevator problem and solution.

- Bring outsiders into the discussion – This is the single most helpful reframe practice. Search for people who understand but are not entirely in your world, and who can speak freely. Don’t expect solutions, but instead, input.

- Get people’s definitions in writing – People commonly leave a meeting believing they all agree with something just to find out months later that they actually had different views. Writing it down can help define differences and look contrarily at the problem

- Ask what’s missing – When facing a problem description, we tend to go deep into the details of what has been stated, perhaps overlooking what has been missed.

- Consider multiple categories – Transforming people’s perception of the problem can bring powerful changes. One method is inviting people to specify which category of the problem they are facing. Is it a motivation problem? A quality problem? An attitude problem? Then try to suggest more categories.

- Analyze positive exceptions – You can look for new insights and try to find instances when the problem did not occur: “What was different about that situation?“

- Question the objective – You can reframe a problem by clarifying and challenging the objectives of all involved parties. The slow elevator problem shows us an objective change from making the elevator faster to improve the waiting time experience.

Becoming skilled at reframing takes time and effort. Encourage your team to trust the method and be prepared for it to feel messy and confusing. Combine the technique with real-world testing; it is limited by the knowledge of people in the room. When facing a problem start by reframing it, but don’t take too long without experiencing the problem for yourself, look at your customers and prototype your ideas.